Paper cuts over cut-and-paste

Abby Schleifer on zines, librarianship, and designing for critical engagement in an age of AI

In early May,

, a librarian and zinester based in New York, wrote a short post on that went unexpectedly wide. In it, she shared a moment with undergrads who had come to the library, unprompted, to photocopy their handmade zines. One paused mid-flip and said, “Zines are kind of like anti-AI.”The post landed—nearly 6,000 likes, hundreds of replies—as educators echoed the sentiment. It named something many were already circling: a hunger for tactile, expressive, unmediated authorship. After semesters of screen fatigue and click-to-submit coursework, zines offered a potential answer to a growing question: how do we bring students back into the classroom?

Zines as pedagogy

Abby made her first zine in a college course on women’s music and literature. She read Audre Lorde and Kathy Acker, listened to punk and hip hop, and made something by hand as her final project. “I chart so much of my journey back to that class,” she says. “It was where I had my musical ethos and awakening.”

In library school, she discovered zine libraries and dove deep into the scholarship. “There’s more of it than people think,” she says. “Zines have been written about seriously for decades. There’s a whole body of literature that takes them seriously as a mode of publishing and cultural memory.”

That ethos carries into her work today. At Pace University, Abby integrates zines across her instruction: designing orientation materials as mini-zines, hosting classroom workshops, and creating assignments that value low-stakes, high-agency publishing. “Whether that’s zine interpretation, zine-making, or just putting a physical zine in a student’s hands—it changes something,” she says.

A library built for browsing

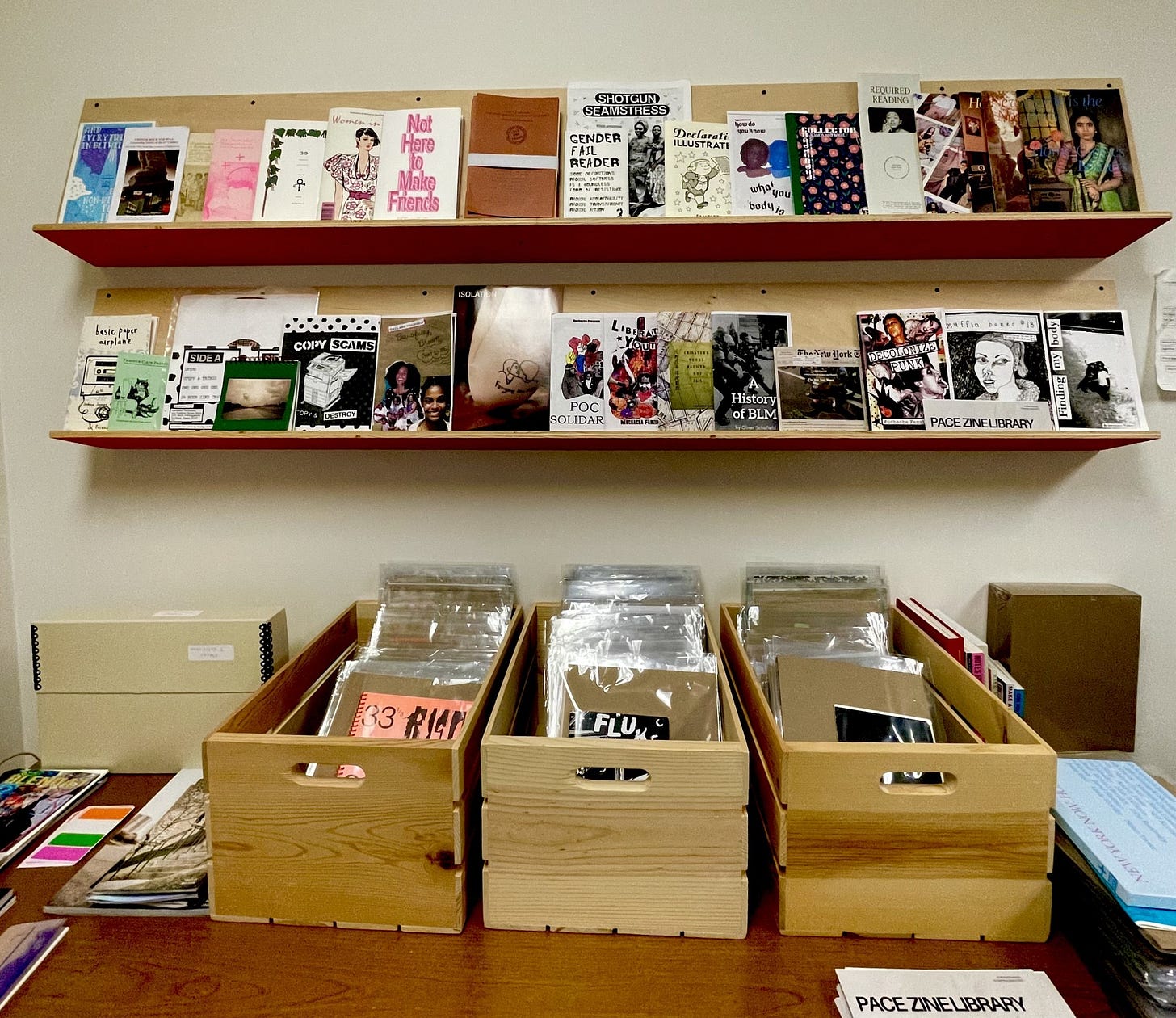

The zine collection at Pace is intentionally tactile. Record-bin style boxes invite students to browse by touch and instinct. You’ll find punk zines and queer manifestos, fashion mags from Loewe, feminist publications from the ’70s and ’80s, and new work from the Black Zine Fair.

Curation is casual, alive: a Pride shelf here, a punk shelf there, a “whatever-we-loved-this-week” shelf. The library’s collection policy is expansive by design. “We have a very broad understanding of what counts,” Abby says. “Zines, chapbooks, small press… we even collect high-production publications if they feel aligned. If it’s self-published, we want to see it.”

Librarians to the front

Abby wants to be clear: She didn’t coin the “anti-AI” framing—her students did—but she gets it. Where generative tools optimize for ease, zines demand effort; where AI blurs authorship, zines insist on it. Still, she prefers the term “pro-agency” over “anti-AI.”

She’s also quick to point out that librarians have always been early adopters: “Librarians have always been on the front lines of tech,” Abby says. “We were some of the first to bring in the internet, to teach databases, to help people navigate search when that was still a skill. The idea that AI makes libraries obsolete completely misses the point.”

At Pace, the library team has a dedicated AI Slack channel, where staff share updates, test tools, and explore how AI is shifting the needs of students. Some are integrating LLMs into instruction. Others, like Abby, are watching from the side, asking different questions.

Beyond the binary

Zines and AI aren’t at odds, Abby says, they’re parallel modes of inquiry. “We have to explore both,” she says. “Students already are.” Some of the most enthusiastic zine-makers on campus are computer science majors, toggling between Python scripts and collaged covers. To them, zines aren’t just a screen break, they’re a way to write, draw, collage, and communicate without predictive text or algorithmic interference.

The real opportunity, she believes, isn’t replacing teaching with LLMs, but reshaping what we teach for: “If you’re only preparing students for knowledge work and that work gets automated, what are you preparing them for?” she asks. “Higher education can’t just be about career prep. It has to be about meaning-making.”

She’s interested in modes of publishing that cultivate interpretation, synthesis, and voice. These skills resist automation.

Print is not dead, after all

The underlying question in all of this is retention: not just academic, but cognitive. How do we help students retain ideas? Curiosity? A sense of ownership?

A recent MIT study measured the effects of using ChatGPT on essay writing and memory. The findings were sobering: 83% of participants who used an LLM struggled to recall what they wrote just minutes later. EEG scans showed a 47% drop in neural connectivity during LLM-assisted writing compared to writing unaided. Researchers called it “cognitive debt,” like technical debt, but for your brain. Each shortcut compounds over time, diminishing memory, reducing attention, and flattening authorship into a string of predictive output. Students write, hit save, and forget.

Abby sees zines as one counter to this: slow, deliberate, personal. “Critical thinking isn’t dead in the land of zines,” she wrote in that initial post. “It’s thriving. Academia has to pivot.” Her view: students should be creating knowledge, not just consuming it. Zines offer a space to practice that kind of authorship, especially for those dulled by rubrics, platforms, and scantron logic.

She’s currently drafting new assignments and connecting with other educators experimenting with alternative publishing. “If anyone’s curious about starting a zine library or using zines in the classroom, I’m always down to talk,” she says. “It’s not as hard as you’d think.” Get in touch with her here and subscribe to her Substack below.

I love the way you include how people are combining tech and handcrafted creations!