Spotting machine-made prose

On linguistic patterns, writing gyms, and why ChatGPT loves tapestries

You’ve seen it: a perfectly ordinary, nondescript sentence. The kind you skim past, then return only to discover it says absolutely nothing at all. An amalgamation of platitudes about “the era of this” and “the era of that.” Now more than ever. If someone asked you to recap what you just read, you’d draw a blank. What was it about again?

Recently I sat down with designer and writer

to discuss the increasing prevalence of AI-generated writing. What started as a discussion about spotting AI patterns quickly evolved into a deeper conversation about writing, thinking, and what we lose when we outsource our voice.The fingerprints of fake prose

Elizabeth identified a particularly grating pattern: The metaphor and tricolon construction. It follows this template: “[Topic] isn’t just [basic description]; it’s [metaphor] that [three related concepts].”

For example: “This isn’t just a screed about AI writing; it’s a manifesto about authenticity, creativity, and the future of human expression.”

Or, “This isn’t just a Substack about why your AI-generated essay is terrible; it’s about what you’re missing by not writing it yourself, the magic of mundanity, and the downfall of society as we know it.”

Once you spot these patterns, they’re impossible to unsee. They populate corporate blogs, LinkedIn posts, newsletters, and especially “slop”—that low-quality media churned out by generative AI. This structure is one of the many fingerprints of fake prose, and those fingerprints are everywhere now.

The tells

As writing becomes increasingly AI-assisted, certain phrases have become tells. In scientific papers alone, usage of the word “delve” jumped significantly after ChatGPT’s release, with nearly half of all papers containing the word appearing post-launch. Paul Graham considers it an immediate red flag in pitches. Designer Nika Simovich Fisher recently noted another tell: “using the word ‘tapestry’ in a metaphor is a clear indicator of ChatGPT.”

Other giveaways of machine-made prose:

Opening with “Picture this:” or “This is where things get interesting”

Robotic transitions: “Furthermore,” “moreover,” “additionally”

Empty scene-setting: “In today’s digital landscape”

Overuse of words like “navigate,” “enhance,” “elevate”

Metaphors involving symphonies, tapestries, or “complex dances”

Uniform sentence structures

Technical tells: Title case, dumb apostrophes, low “perplexity” (predictability) in word choices

The archive anxiety

Elizabeth isn’t just an observer of AI writing patterns—she’s spent years building public archives of design history, from vintage ads to forgotten typography specimens. “I’ve been beating the drum of archival content for six, seven years,” she tells me. “To me, it’s all about humanity, learning, and connection.” Now she watches as these carefully curated archives become training data for AI. “These tools and processes that I’ve been championing are being subverted as shortcuts for people who don’t want to do that work.”

This creates a peculiar form of digital decay: AI learns from human writing, then humans learn to write like AI. If the adage that you are what you consume is true, logic follows that we may very well start adopting or amplifying these AI tropes in our own vocabulary. With approximately 60,000 scholarly papers in 2023 containing AI-generated content, we’re creating a feedback loop where authentic expression gets smoothed away, replaced by what machines think good writing should sound like.

The paradox of digital decay

The real issue with AI-generated content isn’t its polish, but rather its tendency towards mediocrity. In its quest to pattern-match across vast data sets, AI inevitably gravitates towards the average. This approach leads to a loss of texture—smoothing away the idiosyncrasies, unexpected turns of phrase, and leaps of logic that characterize great writing...

The value of good writing

Even in the internet’s smallest corners, people are choosing machine-generated compositions over their own voice. “What fascinates me,” Elizabeth says, “is that people are going out of their way to use AI to post something that will be seen by a very small number of people.”

Elizabeth points to niche video game reviews: “A delightful fever dream wrapped in a cozy blanket of whimsy and hilarity,” she reads aloud. “Look, one person marked it as helpful.” (Through the screen share, I can see that Elizabeth has down-voted the review—doing her part to maintain the status quo.) She contrasts this with a human-written review: “‘The character shoving sausages through the fence is a bit creepy.’ Isn’t that so much better?” It’s true. The latter, depicting a sausage glory hole of sorts, is undoubtedly less vague, and gives a much better idea of what to expect with the game.

“What does it mean that people now feel compelled to use AI to express themselves, even in these corners of the internet that aren’t commercially viable for them?” We run through the logic: Someone clearly played this game and wanted to share that joy with others or at least leave a review—but were they not confident enough to write the review themselves? Why did they resort to AI?

The mass adoption of AI writing tools even for the most mundane writing tasks raises questions about what we value in writing. What makes writing good? As AI models mimic whatever we as a society choose to hold up as our shining examples, this question becomes increasingly consequential. We are actively shifting the goalposts for what we collectively perceive good writing to be—whether we intend to or not.

Machine-driven mundanity

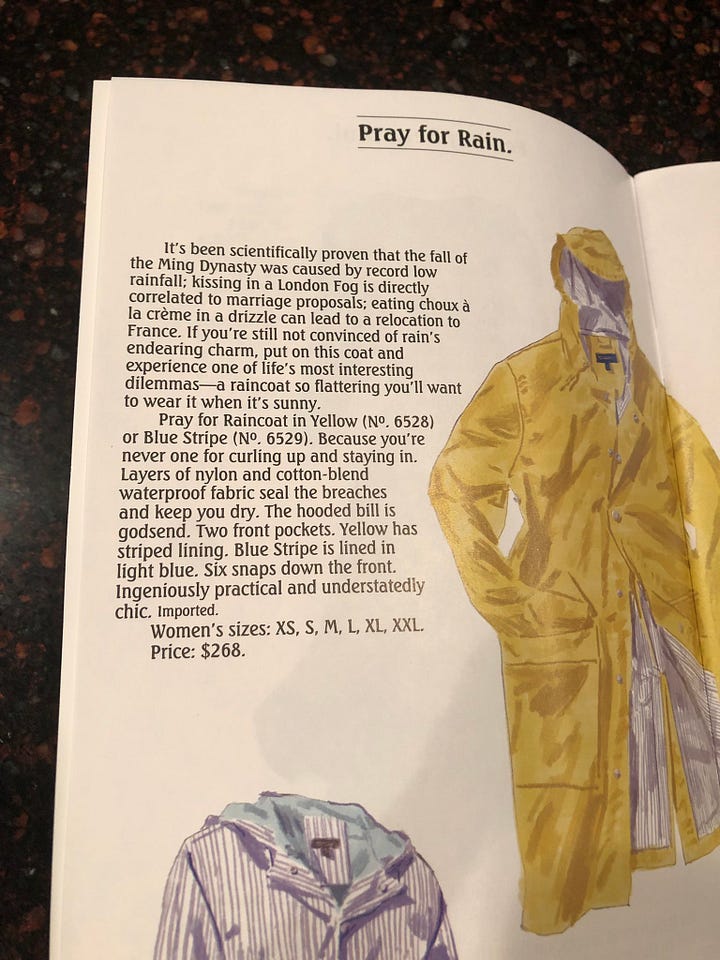

Humans thrive within constraints. Some of the best writing comes from humans making mundane things interesting. Elizabeth points to the J. Peterman catalog, famous first for its presence on Seinfeld, but more importantly for its distinctive voice in product descriptions: “People say ‘so much writing is formulaic, who cares if we use AI copy?’ But the J. Peterman catalog shows how the best art can emerge from mundane stuff—someone who was a writer probably hated that job, but they had to do it, so they made it interesting for themselves,” says Elizabeth.

This gets at something essential that AI can’t replicate—the human impulse to find meaning within constraints, to make something engaging not because an algorithm said it would work, but because a person decided to make it so. When every product description becomes a “journey” and every feature a “testament,” we lose the unexpected moments where a determined copywriter created something genuinely strange and wonderful.

The muscle memory

“I don’t actually know what I’m writing about until I sit down and write it,” Elizabeth says. “Almost every writer you talk to will tell you the same thing.” This idea—that writing is fundamentally a process of discovery—runs counter to how AI approaches text generation. AI can remix existing ideas, but it can’t discover new ones. It can’t have that moment of clarity that comes from wrestling with a half-formed thought until it finally makes sense.

As Paul Graham notes in a recent essay, there’s a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing. He predicts a future split between “writes and write-nots”—where the only people who write are those who choose to, like going to a gym to hone physical strength. Elizabeth compares writing to running: “I feel accomplished for having done this, I’m happy with the result. But everything I have to do to get there kind of sucks. When you’re running, you know you’re exercising. There’s nothing else there.”

In his essay, Paul quotes computer scientist and mathematician Leslie Lamport: “If you’re thinking without writing, you only think you’re thinking.” In our conversation, Elizabeth says something similar: “The idea that writing is simply a matter of transcribing is a thought exclusively held by people who don’t write.”

Write from wrong

Elizabeth sees this playing out in her RISD classroom. Recently she assigned her students to present an opinion on any topic. Some students turned in presentations clearly written by AI—some didn’t even bother to edit out the default text that read “you might consider doing a project that involves [blank].”

For a project where the one requirement was to have an opinion, there’s an irony. AI has only the opinion of the dataset, the average. The issue isn’t that the presentations were bad (they were)—it’s that the students missed out on an important opportunity to discover something about their own beliefs. In response, Elizabeth addressed her class directly: “Your ideas will be stronger if you are developing them further from what ChatGPT is telling you.” A gentle way of saying there’s no shortcut to finding your voice. You have to do the work to develop the muscle.

Finding your voice in the machine age

So where does this leave us? Elizabeth admits that she finds generative AI tools helpful in small doses—getting past blank page anxiety, pulling themes from transcripts—but estimates that only about 10% of the output is actually useful. “I don’t think there’s anything necessarily unethical about using AI for synonyms or transcriptions.” she says. “But I do have anxiety around being like, ‘Wow, I can’t believe I just dumped out a water bottle to ask what another way to say complicated was’—that’s where I feel guilty that I use it at all.”

As with any paradigm shift, there are compromises. The writing gym metaphor becomes particularly apt here: you can use machines to assist your workout, but they can’t do the work for you. The value comes from the effort, the struggle, the gradual building of capability. The issue isn’t whether people can write, but whether they believe their own voice is worth preserving.

That’s the existential question facing all of us who write, teach, or build archives: How do we preserve human creativity in a time that increasingly prefers machine-made perfection? The answer might lie in Elizabeth’s approach to her students. She doesn’t ban AI—she just reminds them that their messy, unpolished thoughts might be worth more than any perfectly optimized prose. Sometimes the most valuable thing isn’t the polished final product, but all those human fingerprints smudged across the process.

—Carly

Great article. “Watch your thoughts; they become your words; watch your words, they become your actions; watch your actions, they become your habits; watch your habits, they become your character; watch your character, it becomes your destiny.”

Carly you’ve been SMASHIN it. And yay to a Carly × Elizabeth intellectual collabo!!

I’ve long admired people who can write like they talk, and aspire to do that myself. I don’t consider myself a writer but I do value my voice and what it sounds like!