The generalist renaissance

Founder Mode, design engineers, and your next career pivot in the age of AI

It seems like every day I see a new AI demo on my feed, revealing yet another task that can be outsourced to an LLM. From existential podcasting to improving upon your circus poster, it’s enough to make anyone question their skill stack and wonder which jobs AI might come for next.

Conventional wisdom suggests doubling down on a niche is the safest bet. After all, someone with middling competence across multiple domains seems likely to be outpaced by an AI language model. But what if these very generalists are poised to inherit the digital earth? Welcome to the generalist renaissance, where being a dabbler might just be the smartest career move.

Full disclosure: I’m a self-described generalist. For years, I’ve ping-ponged between design and writing in all its forms, often feeling like an impostor in both. I used to describe myself as a “specialized generalist or generalized specialist generally specializing in...” followed by whatever had my attention at the moment. And—dare I say—it finally seems like it’s starting to stick?

The shifting value of human expertise

Recent discussions in tech and entrepreneurship circles suggest a resurgence of the generalist. From startup accelerators to Design Twitter™, we’re seeing calls for multifaceted founders and job listings for hybrid roles.

Dan Shipper, Co-founder and CEO at Every, argues that “in the age of AI, it’s better to know a little about a lot than a lot about a little.” He cites David Epstein’s book, Range, which explains how generalists excel in “wicked” environments with unclear rules, non-obvious patterns, and delayed feedback.

Sound familiar? It should, because that aptly describes our current technological and economic hellscape—errr… landscape. While AI excels at deep, narrow knowledge, it flounders in the murky waters of interdisciplinary thinking and novel problem-solving. Generalists, on the other hand, are the curious folks who connect dots between disparate fields, seeing patterns where others see chaos. A niche in itself.

The founder as ultimate generalist

Y Combinator Co-Founder Paul Graham’s essay “Founder Mode” challenges the notion that scaling a company requires founders to step back and delegate most responsibilities. Instead, he suggests that successful founders maintain deep involvement across various aspects of their businesses, effectively functioning as high-level generalists.

This aligns with trends I’ve observed in the design world, where the best studios often have founders who remain deeply involved in both creative and business aspects—and even spin off other projects or endeavors. Take Cameron Koczon, friend and Founder of Fictive Kin and Kinference and teudeux. Or Emmett Shine of Little Plains and Pattern and formerly Gin Lane, David McGillivray of Corners and OFFHOURS, or Rachael Yaeger of Human NYC and Roscoe Motel and whatever she thinks of next… These multifarious founders have their fingers in everything, giving them not only a bird’s-eye view into their own operations, but also the ability to speak designer, developer, and client—sometimes all in the same meeting. They pivot when the market shifts, spot opportunities others might miss, and connect dots no one else saw. In the world of design studios, that kind of versatility isn’t just useful—it’s survival.

The rise of the design engineer

The design engineer epitomizes generalism in 2024. While not new, the title sparked discourse™ earlier this year when Vercel published an explainer. These individuals combine “aesthetic sensibilities with technical skills”—not only envisioning interfaces but also bringing them to life. Atlassian’s Head of Design for AI, David Hoang, predicts:

“Design engineers will be the most sought after role this decade.”

Why the sudden open arms? Turns out, there are benefits to having someone on the payroll who can build their own ideas. As tooling evolves (yes, we’re still talking about AI), the divide between design and code narrows. Tools like GitHub’s Copilot and Figma’s First Draft bridge this gap. As the one-man idea-builder himself Jordan Singer tweets: “you’ve now been upgraded to a design engineer if you simply choose the right tools.”

Product builders who know a little bit of design and development are best poised to take advantage of this shift. A dedicated dabbler knows the right tweaks to tease out the desired output from the AI slop machine. For them, AI acts as an accelerant, extending their skills and amplifying their vision—nothing lost in translation.

Does this render either role irrelevant? Of course not. “There’s so much more to being an engineer than just outputting code…The best engineers are ones who can reason from first principles about the higher-order domains they are working on without over-rotating on the nuance of a specific manifestation of that domain—a language, framework, or platform du jour,” writes Figma CTO Kris Rasmussen.

The same applies to designers and any generalist straddling multiple disciplines.

What’s in the box?

As new openings for design engineers appear, roles for the rest of us generalists remain scarce. As the other Airbnb co-founder told me after reviewing my college portfolio circa 2013, “The work is cool, but I have no idea what I’d hire you to do.” To land a job, I had to use the right language: brand strategist, writer, copywriter. (My job titles have included “Writer III,” “Content Strategist,” and “Content Designer.”)

This challenge is common. A survey found that 56% of generalists believe there’s no clear career path for them, with 35% feeling excluded from promotions. Most companies still operate with headcount assigned to specific roles that align with ladders and salary bands—roles that rarely have “generalist” in their titles. The larger the company, the more structure (in other words: the harder it is for a generalist to squeeze into a specialist-sized hole).

Another hiring risk: To be a generalist is sometimes to be a master of none, slinking into the background, and being the no-stats all-star on a team. As Designer Trevor Rogers puts it: “You won’t be the MVP, but you make everyone better by being versatile and reliable. Your impact is crucial, but rarely in the spotlight. You’re the Derek Fisher of design.” But try translating that into a promotion.

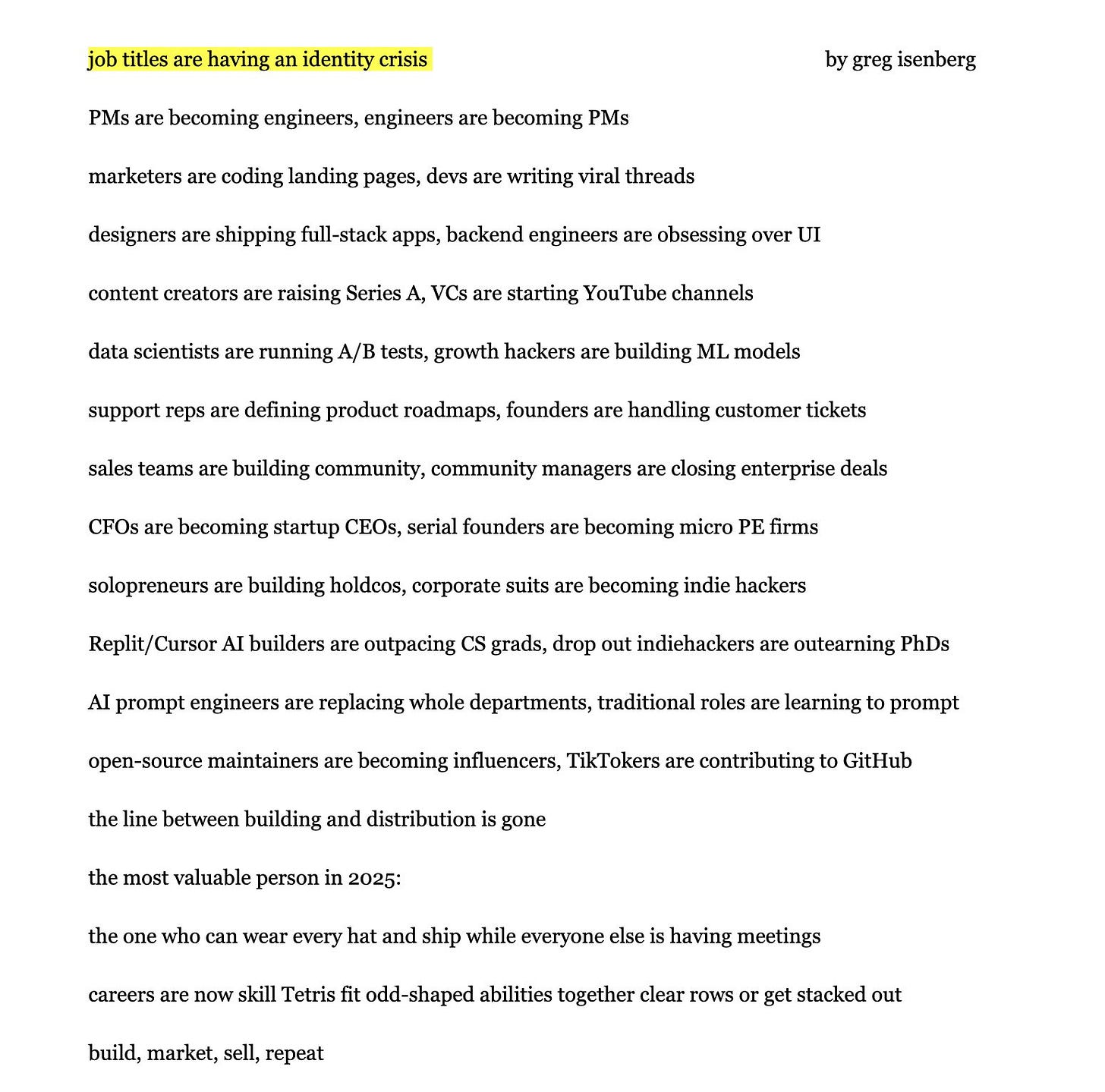

However, change is coming. Vercel’s listing suggests a shift. This week I saw Linear hiring for an “Operations Generalist.” Perhaps, as Greg Isenberg predicts, the most valuable person in 2025 is “the one who can wear every hat and ship while everyone else is having meetings.”

Long live the multihyphenate

In a world where specialized knowledge has a shorter half-life than ever, the ability to learn quickly, make unexpected connections, and adapt to new situations is the generalist skill stack most likely to set you up for success. It’s less about what you know and more about how quickly you can learn what you need to know.

As Dan Shipper puts it:

“In an allocation economy, the person who wins isn’t the expert who knows the exact answer to a question. It’s the one who knows which questions to ask in the first place.”

This is a bit of a paradox, though, because part of knowing the right question to ask is, quite literally, what you know. So perhaps the key is not to abandon specialization entirely, but to cultivate a T-shaped skill set: deep expertise in one area, with a broad understanding of many others. In the age of AI, it’s not about knowing everything—it’s about knowing how to learn anything, and more importantly, knowing which questions to ask.

—Carly

Oh wow my ADHD may finally pay off!

I am in a community called Generalist World. It’s been a boon for my professional confidence and self-understanding. Would recommend it to folks who resonate with this post!