The latest design problem? Getting a job

On design hiring and getting a job in 2026

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times—for designers, that is. We had been cooked, but now we were back. So back. Paul Graham shared-an-essay-on-taste-levels-of-back. Sure, we always knew that our work had value, but now it’s becoming clear to everyone else: In a world where you can make anything, design is what helps you identify and make something actually worthwhile. So why is it still so hard to get a job as a designer?

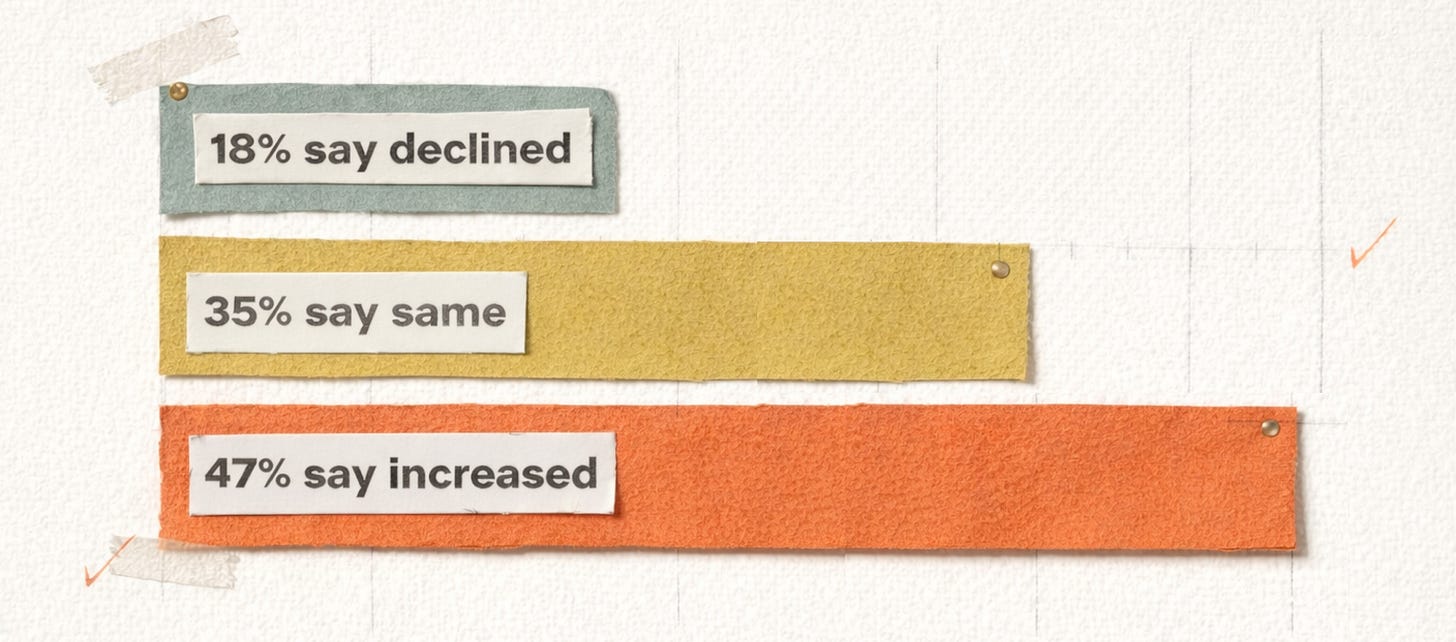

That tension—renewed respect for design alongside the bleak hiring picture—defines what it feels like to look for work right now. Big tech still trimming. Agencies grinding. “Open to work” avatars flood LinkedIn. Meanwhile, hiring managers are posting roles and founders are offering four-figure bounties for referrals. Some designers can’t get a reply; others are swatting away inbound. And the chasm between the two keeps growing.

Last year, I wrote about the market shifting from narrow execution skills toward designers who can ship outcomes in an AI‑driven world. Since then, what that actually looks like in practice has come more into focus. What exactly does it take to get hired as a designer in 2026?

The good and the bad

If you are a designer looking for work right now—you’re not alone. I’ve talked to many of you and, yes, it sucks. You’re firing off hundreds of applications and hearing nothing back. Or worse, investing hours on take-homes, prepping for day-long on-sites, only to get ghosted or roasted or both. Feedback, if it comes at all, is vague enough to be useless.

But companies are hiring, especially in high-growth orgs. Demand for designers is climbing across industries—not just in tech—and the fastest growth is coming from teams that see design as a way to move faster, differentiate, and turn fuzzy AI ambition into real experiences. When anyone can press a button and generate “good enough,” the premium shifts to people who can tell what’s good, what’s useful, and what’s worth shipping. In other words: designers.

The new job requirements

Production is cheaper. Execution is abundant. The scarce skill becomes deciding what’s worth making and why. Hiring loops have adjusted accordingly.

I consulted my local subject-matter expert (and husband) Sebastian Speier on what he sees companies actually screening for. He broke it into three buckets:

Product sensibility: Can you think like a product manager—anticipating business needs, aligning goals with product decisions, while balancing user needs?

Design at the speed of conversation: Can you spin up a prototype or sketch in a meeting that steers decisions, making the problem legible in real time?

Craft: Is it impeccable? Can you see the difference between good and great?

High agency has gone from buzzword to table stakes. At lower levels, designers are told what problems to solve and solve them. At higher levels, they expand scope, identify problems, and jump into the most important ones without being asked.

And then there’s AI fluency: are you using AI tools to prototype, push fixes, and unblock yourself—or waiting on someone else to move work forward?

Product sensibility

The designers who stand out can reason through fuzzy problems, make smart tradeoffs, and balance delight, feasibility, and impact. This is the difference between someone who executes a brief and someone who shapes it—knowing what to build first, what to cut, and why it matters.

The clearest signal of product sensibility is how a designer defines the problem they’re solving. “I built a Foursquare competitor” tells a hiring manager almost nothing. Who needed it? What were they actually trying to do? Why did existing options fail them? Answering those questions is what separates a portfolio that shows execution from one that shows judgment—and it’s what good PMs and designers have in common. Great case studies make this legible: not just what shipped, but what didn’t, and the logic behind both.

Design at the speed of conversation

The expectation has shifted from delivering work after the meeting to steering it during. Designers who stand out show up with a prototype, sketch in real time, and leave the room with alignment because they made the problem legible while it was still open. PRDs are cheap. Prototypes drive decisions.

This skill is hardest to show in a portfolio, but the best case studies gesture toward it: a specific user, a real constraint, a clear before-and-after. Kasey Klimes, design researcher and technologist, describes the underlying dynamic: “It used to be that weak thinking could be obscured by impressive execution, while strong thinking could get lost in poor execution. Now, the execution is so universally impressive that it recedes into the background to reveal the thinking.”

Craft

Craft is the discipline of someone who has put in the reps, who knows what good looks like and can reliably get there. Not just polish, but instinct. The details are right because the designer couldn’t leave them wrong. Call it taste. This is the hardest thing to fake in a portfolio review and the easiest thing for a hiring manager to spot when it’s missing.

Getting a job as a designer is a design problem

Getting a job as a designer is, itself, a design problem. “If you can’t figure that out, you can’t solve problems for other people,” says Sebastian.

Treat it like any other brief. Understand the constraints and the stakeholders: What does this team value? How do they talk about their work? Where does this role sit in the larger system? Then make things—portfolios, case studies, emails—and ship them. Pay attention to what lands and refine from there. Instead of waiting to be discovered, design the signals that tell your story. Iterate until the system fits. As Sebastian puts it: “You need to be able to sell yourself. It’s the only product you’ll ever be able to fully control.”

F*ck it, ship it

In 2026, your job search is a product you have to ship. The market no longer rewards potential; it rewards shipped outcomes. The designers getting hired are the ones already in motion. For everyone else, the gap often isn’t talent, it’s approach. Define the user, clarify the value proposition, prototype your positioning, iterate on signal. The jobs are out there.

It’s a great time to be a designer

Turns out, the robots are great at making more, but terrible at making it matter. “Slop” was Merriam-Webster’s 2025 word of the year for a reason. Consumers are craving authenticity; brands are following suit—hand-drawn type, irregular marks, real texture. The age of synthetic sludge is losing its sheen.

AI has made mass production trivial. That means taste—clarity, judgment, restraint—is rare again. The world is looking for designers who can bring humanity to an abundance of artifacts. And that makes it, strangely enough, a great time to be a designer.

Designers in the market: what am I missing? Let me know.

As usual, much of the thinking in this piece started as a conversation with Sebastian, who has the rare skill of making fuzzy things legible in real time. Happy belated Valentine’s Day.

Appreciate this write up!! IMO an under discussed aspect of this is that the industry has lost any interest it once had in apprenticeship. Anyone at the "top" is there because someone took a chance on them early in their career, and we should all be paying that forward. How do we expect to have an abundance of good, senior designers if we're not willing to train them?

Great insights! I also believe that designers who showcase their personal projects are more appreciated than those who have created lengthy case studies in a corporate setting. I've experienced this shift myself and need to update my own portfolio.