Feeling a bit crispy lately. Maybe it’s that we’re reaching the end of summer, or that I’m getting married in 19 days (!), but the edges are fraying, my friends. My patience is wearing thin, so please bear with me while I vent about something that has been needling me (it’s AI), and then I promise I won’t talk about AI for at least another week.

Genesis of a crispy concept

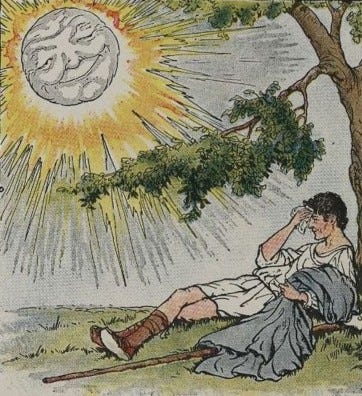

It all started during one of my daily AI tussles. The harder I pushed for coherent output from Claude, ChatGPT, Perplexity—or any of the LLMs I’ve come to rely on—the more generic the results. It was like the fable where the Sun and North Wind compete to remove a traveler’s cloak—the more force applied, the tighter the grip.

With each follow-up prompt—tweaking tone, order, structure—the worse my output became. I shared this with my fiancé, Sebastian, who offered a peculiar comparison: deep-fried memes. The more these memes are remixed, the more culturally valuable they become—while AI content, though more polished, becomes less interesting. This got me thinking about two divergent paths: digital decay enhancing meaning, versus digital perfection erasing it.

The crispy currency of deep-fried memes

Deep-fried memes, born on Tumblr circa 2015, are intentionally degraded, their garish colors and overblown compression artifacts mocking the natural degradation that occurs when memes are shared, screenshot, and re-uploaded ad infinitum. As each layer accumulates, it adds provenance, a watermark of their journey across the web.

This phenomenon mirrors filmmaker Hito Steyerl’s “poor image” concept. Low-resolution, degraded images gain cultural value through circulation. Researcher Saskia Kowalchuk pushes this idea further, saying a deep-fried meme is “a poor image brought to its logical extreme.” In our digital economy, these deep-fried memes are a currency all their own. A well-timed, crispy meme in the group chat? Priceless.

The paradox of AI-generated polish

But when it comes to AI, the opposite happens. As models like GPT-4 and its successors evolve, they produce increasingly polished content. Yet this “polish” strips the output of its uniqueness and character, making it less valuable, less interesting. Recently, Dylan Field, CEO of Figma (where I work), tweeted a poll asking if “written by Claude” (an AI) was a compliment or insult. The result? 68% saw it as an insult.

This begs the question: What makes AI-generated content so... unsatisfying? Is it our ego bristling at the idea of machine-made prose? Or is Claude simply not a very good writer? What even constitutes “good writing” in this brave new world?

The mediocrity of the mean

The real issue with AI-generated content isn’t its polish, but rather its tendency towards mediocrity. In its quest to pattern-match across vast data sets, AI inevitably gravitates towards the average. This approach leads to a loss of texture—smoothing away the idiosyncrasies, unexpected turns of phrase, and leaps of logic that characterize great writing. What’s left is technically correct but soul-crushingly dull. In trying to be “good,” AI aims for what’s common, rather than what’s compelling.

As AI language models evolve, they’re becoming more constrained, less creatively daring. Earlier versions could spit out wild and unexpected prose, but as these models get fine-tuned, their responses become more uniform and predictable. Take Vauhini Vara’s experiment with GPT-3. She co-wrote a deeply personal essay about her sister’s death, which became her most successful work. But as newer models were released, Vara couldn’t recreate the same quality, finding the output boring and full of clichés, even after repeated attempts.

As AI content is recycled and reprocessed, it doesn’t become more refined in any meaningful way. Instead, it gets increasingly generic, losing the nuances that make it worth reading. Ergo, “deep-fried AI.” It’s a self-consuming loop of context, an ouroboros algorithmic regurgitation.

The compounding problem of training on mediocrity

This issue compounds as AI models are increasingly trained on datasets that include AI-generated content. In AI, this leads to what researchers call “model collapse.” The AI, trained on its own outputs, starts producing increasingly generic, error-prone, and ultimately meaningless content.

Ilia Shumailov, a computer scientist, describes it as such: “If you take a picture and you scan it, and then you print it, and you repeat this process over time, basically the noise overwhelms the whole process. You’re left with a dark square.” Each generation loses some fidelity, some connection to the source material. Poor images, indeed.

The human touch in art and writing

This weekend, Ted Chiang published an essay in which he argues that AI is fundamentally unable to create genuine art. He points out that art is the result of numerous choices—some large, but most small and intuitive. AI, in contrast, allows humans to make few choices, delegating the bulk of decision-making to pattern-matching algorithms. He writes, “The selling point of generative A.I. is that these programs generate vastly more than you put into them, and that is precisely what prevents them from being effective tools for artists.”

Human creativity often lies in the outliers, the unexpected connections, the novel perspectives that deviate from the norm. AI-generated content, in its polished perfection, lacks these qualities. It’s a pastiche of patterns, devoid of the spark that makes truly great creative outputs stand out.

The bizarre beauty of AI hallucinations

While AI may fail at generating compelling prose or art, it occasionally produces “hallucinations”—moments of bizarre, off-kilter output that are both fascinating and alarming. These glitches in the matrix reveal the limitations and biases in AI training data, sometimes reflecting ourselves and internet culture back in surprising ways—from fabricated legal documents to rick-rolling customers.

Ironically, these AI failures can be a source of creativity. Artists are already drawing inspiration from AI-generated hallucinations, and there’s a growing trend on TikTok of people imitating AI and interpretations of these digital fever dreams.

In praise of digital patina

Perhaps the most valuable digital experiences are those that bear the marks of their creation and circulation. With memes, we’ve seen how a “digital patina”—the accumulated traces of creation, use, and sharing—adds value. Rather than aiming for polish, maybe we should be striving for texture, history, and provenance.

One possibility is to trace the origins of AI content, marking each iteration with metadata about prompts used, choices made, and iterations run. Another might be curating smaller, more focused datasets. We could even introduce deliberate stylistic noise to mimic the variations in human writing. Imagine AI systems that generate not only polished outputs but also show traces of the backstory that brought it into being.

In the world of deep-fried memes, degradation adds value. In AI-generated content, however, polish detracts from it. The challenge ahead lies in recognizing that value often comes from imperfection, texture, and quirks—the very things that AI currently erases. The key might be to embrace the crispy, the flawed, and the human touches that make digital content worth engaging with in the first place.

Stay crispy (but not too crispy),

Carly